As companies increasingly see the value of pursuing product agility over project management, the role of a Product Owner has gained significant prominence. A Product Owner serves as the customer’s advocate—the ultimate champion of value delivered—and helps coordinate between the product teams, steering the product’s vision and driving its success. While hiring external candidates with Product Owner expertise is an option, many organizations fail to train or develop their internal employees as new product owners.

We will explore some steps organizations can take to identify existing employees that have the right mindset & institutional knowledge, and equip them with the skills required to become effective Product Owners.

Identifying potential candidates

The first step in developing a strong pipeline of Product Owners is to identify employees who possess the necessary skills and mindset. Look for individuals who demonstrate a deep understanding of the organization’s products, show strong communication and collaboration skills, and possess a customer-centric mindset.

Where to find potential new product owners

These individuals may come from diverse backgrounds, such as project management, business analysis, or software development. But there are some less obvious choices that are often overlooked:

Call Center and or Customer Support teams are a great place to find potential new Product Owners. The people in these roles speak with your customers all day every day, and hear firsthand what they love and what they would like to see improved. They should have deep knowledge of your products that can translate well to the Product Owner role.

Marketing roles are very similar in their product knowledge, with an added view into the market landscape and industry trends.

Another overlooked role are your QA testers. They review changes to your products to ensure they meet the user needs and are intuitive to use.

Core skills these candidates must possess

Here are some core skills to look for:

- Strategic Thinking: Product Owners must have a strategic mindset and the ability to think long-term. They should be able to define a clear vision for the product and develop a roadmap to achieve the desired goals.

- Communication: Strong communication skills are essential for Product Owners to convey their ideas effectively and collaborate with various stakeholders, including engineers, designers, marketers, and executives. They should be able to articulate the product vision, gather requirements, and facilitate cross-functional teamwork.

- Leadership: Product Owners need to lead without direct authority. They should inspire and motivate their teams, provide clear direction, and make decisions that align with the overall product strategy. Effective leadership helps drive the team towards success.

- Problem solving: Product Owners encounter complex problems regularly and must be skilled at breaking them down into smaller, manageable parts. They should be proactive in finding solutions and evaluating potential risks and trade-offs.

- Adaptability: The product management landscape is dynamic, and great Product Owners can adapt to changes quickly. They should be open to feedback, iterate on their approaches, and embrace new methodologies and technologies.

Providing comprehensive training for new Product Owners

Once potential candidates have been identified, it is crucial to provide them with comprehensive training tailored to the role of a Product Owner. The training should cover a range of topics, including agile methodologies, product management principles, user research techniques, and stakeholder management. Interactive workshops, seminars, and online courses can be utilized to impart knowledge and build practical skills.

Focus on enhancing key skills

Here is a list of five skills a good Product Owner should build:

- Market and user understanding: Understanding the market landscape and the needs of the users is crucial for Product Owners. They should conduct market research, analyze user feedback, and stay up-to-date with industry trends to make informed decisions.

- Analytical skills: Product Owners must be comfortable working with data and making data-driven decisions to determine value & opportunity. They should be able to analyze metrics, conduct A/B tests, and interpret user behavior to gain insights and drive product improvements.

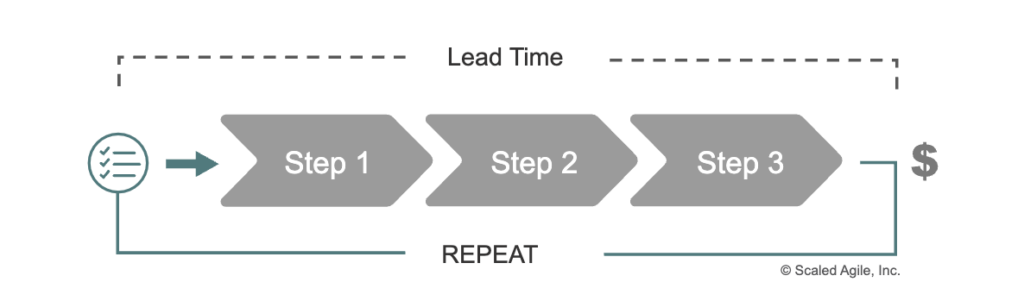

- Prioritization & time management: With numerous competing priorities, Product Owners must excel at prioritization. They should identify the most impactful features or initiatives, allocate resources effectively, and manage timelines to ensure timely delivery.

- Technical understanding: While not always required, having a solid understanding of the underlying technologies and development processes can be advantageous. It helps in effective collaboration with the engineering team and in making informed technical decisions.

- User experience (UX) knowledge: Product Owners should have a good understanding of UX principles and be able to advocate for a great user experience. They should work closely with UX designers to ensure the product meets user needs and is intuitive to use.

Coaching and mentoring opportunities

To supplement formal training, organizations should provide coaching and mentorship to aspiring Product Owners via coaches that specialize in product development. Product Agility Coaches are an excellent resource that can draw from their real world experience to guide the new Product Owners in their new daily activities.

Another way to help aspiring or new Product Owners is to provide shadowing opportunities. Seasoned Product Owners within the company can serve as mentors, offering guidance, company specific experiences, and providing valuable feedback. Additionally, allowing aspiring Product Owners to shadow experienced professionals during product development cycles can provide hands-on learning experiences and foster a deeper understanding of the role’s responsibilities.

Cross-functional exposure

Product Owners need to collaborate effectively with various departments within an organization. Therefore, it is beneficial to expose aspiring Product Owners to cross-functional teams and diverse projects. Encourage rotations to different departments, such as marketing, design, engineering, and customer support. This exposure will enhance their understanding of different perspectives and enable them to make more informed decisions when defining product roadmaps.

It is important to continue this communication and collaboration with these other departments. It should not only be something that prepares them for the role. Maintaining strong lines of communication with these groups will enhance the Product Owner’s broader understanding of their product’s needs.

Encouraging continuous learning

Learning should not stop after the initial training phase. Organizations should promote a culture of continuous learning and improvement among their Product Owners. Encourage them to attend conferences, participate in industry events, join professional networks, and pursue relevant certifications. Additionally, establishing internal communities of practice or knowledge-sharing platforms can facilitate ongoing learning and collaboration among Product Owners.

Performance evaluation criteria

Regular performance evaluations should be conducted to assess the progress and development of aspiring Product Owners. Objective criteria, such as the ability to deliver successful products, stakeholder satisfaction, and effective collaboration with the development team, can be used to measure their performance. Recognize and reward achievements while providing constructive feedback for improvement. Additionally, organizations should create growth opportunities for Product Owners, such as advancement to senior roles or involvement in strategic initiatives.

Conclusion

Training internal employees to become new Product Owners:

- Unlocks the potential of talented individuals within an organization

- Fosters a culture of innovation and collaboration

- Nurtures a strong pipeline of skilled Product Owners

- Ensures a deep understanding of the company’s products

- Drives innovation

- Reduces the overhead associated with external recruitment

- Strengthens employee retention and loyalty

By providing a clear pathway for career advancement and professional growth, organizations can cultivate a culture of internal talent development and create a competitive advantage in the market.