Product Planning Over Project Planning

Product thinking—and its direct result, product agility—is a paradigm shift for companies that previously relied exclusively on project management to plan and manage long-term initiatives. And it’s proven to be highly effective and beneficial.

But, many struggle to establish true product thinking in their organizations. One of the biggest roadblocks they face is how planning needs to change to support this new way of working.

To dive deeper into this subject, check out our webinar, Project to Product: Don’t You Dare Mess with Planning.

How product planning differs from project planning

The planning process under the product paradigm is quite different from traditional project planning and management. But that doesn’t mean it’s a foreign language. There are still elements of a familiar project plan that need to be addressed. However, the key differences can take some getting used to—both for those doing the planning and the executives who need to approve and judge the results achieved.

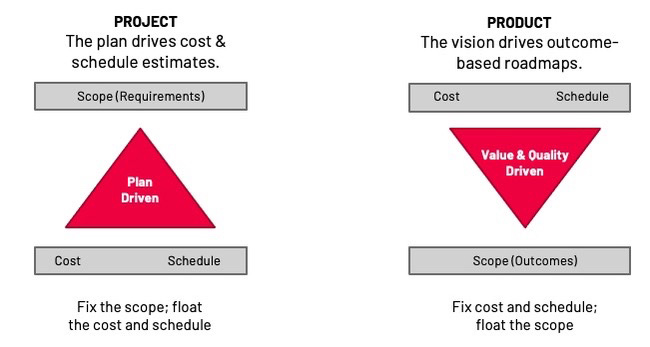

A clear explanation of these fundamental differences is illustrated here:

These same general factors apply to both project planning and product planning. But, the picture on the right is quite different from the one on the left.

Let’s take a look at these three elements and see how they compare under both paradigms:

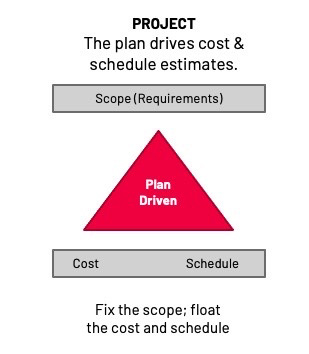

Project Planning

The scope becomes the fixed element in a project plan and provides the ultimate measure of success and completion. After all, the project manager is getting approval from the executives by promising, “this is what I’ll be able to hand you in ____ months if you give me $_____.”

Beyond the fact that budget and schedule are likely to be impacted in the long run, this is problematic for three reasons:

-

- It requires a considerable amount of upfront planning which necessarily depends heavily on estimation.

- As work progresses, a fixed set of requirements and a “guaranteed” final solution hamstrings the team’s ability to respond to learnings and market changes with agility.

- By the time the long-term set-scope project reaches completion, things may have changed so much that the solution needs to be heavily reworked or even scrapped.

In the real world, things change. If a project is planned based on a preset list of requirements, change results in less value being produced for the customer and the company. The customer may not end up with a solution they want or need. The company is forced to invest upfront for an extended period with the possibility of little or no return on that investment.

So, how does product planning compare?

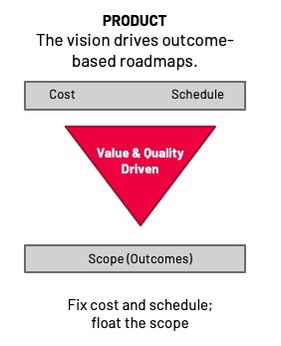

Product Planning

In product planning, planners can effectively fix both cost and schedule because product budgeting is based on the agile teams doing the work. Product managers know how much it costs to employ a group of individuals, and they can set the schedule based on how much they want to spend or just set a future date as an initial spot to plan toward.

This leaves the scope variable. But, importantly, that doesn’t mean no one knows what’s going to be produced or whether or not it’s ever going to be “finished.” It means that teams can fully incorporate agile principles into the production process.

Rather than producing a detailed project plan based around a list of features and requirements that must be in the finished solution, product planners create a prioritized backlog of epics and user stories that will result in a useful and valuable solution as quickly as possible. Then, with feedback loops in place, that backlog can be continually refined and reprioritized to ensure the teams are always working on the right thing at the right time. Even if significant changes are required based on that feedback, these lessons are learned early with minimal wasted investment.

As a result, when things change—and they always do—the initiative’s scope is agile enough to accommodate and make the most of the change.

This is a deep and rich subject with more you can learn if you want to dive deeper. Our recent webinar, Project to Product: Don’t You Dare Mess With Planning, is a great place to start. And, for other related topics, we encourage you to explore our Project to Product resources page.